Using Principal Component Analysis to Save Space on my Phone

A Problem of Space

From Oct 2024 until May 2025 I traveled around the world visiting destinations as well-worn as Rome and Paris to the more esoteric backpacking hidden gems such as Luang Prabang and Tangier. I had just graduated from Georgia Tech with a Masters of Science in Analytics and I needed a long break and the opportunity to celebrate my achievement in a big way. As one might expect, I took a lot of photos and videos. My phone storage availability, already over half-occupied at 35% free, shrunk to an even more critical 15% free.

Before I was even back home, I knew I had a data problem on my hands that I could address with some newly learned methodologies. What data solutions could I implement to identify and execute space saving strategies in my phone? This wasn’t a search for the most optimal solution - which would’ve been to move some of these new photos and videos (or old ones) to external storage, which I have plenty of. I wanted to use this as an opportunity to implement (and teach about) a cool methodology I’d learned during my last few semesters at Georgia Tech: using Principal Component Analysis to downsample photos.

What’s Important vs. What’s Extraneous?

How do we process information when we look at any given thing? Do we visually scan every single detail and commit it to memory to recall upon perfectly later? No, because then we’d have photographic memory. More likely, we visually scan and process information at a high level, remembering the most pertinent information (maybe) and perhaps failing to recall the rest. Does that make the rest of the information irrelevant? Well, honestly that depends on the goal. Let’s take an image of a painting for example.

Here we have Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, a painting everyone is familiar with. But have you really processed the information in this photo? Could you describe to me the angle of particular brush strokes, how broad or thin they are, how long? No, because this information is not relevant to you as far as appreciating this art work goes (from the layman’s perspective). If you were a fellow artist, or even an art historian, those nebulous details might be of much more importance to you. As far as the average person is concerned, it’s a moot point whether this art was made in the post-impressionist style or pointillism. Which is to say that there is visual information we don’t strictly need to achieve the objective of appreciating the art.

I took a lot of pictures of art in my travels. Likewise, in any museum I went to, for any picture of art I took, subsequently afterwards I always took a picture of the artist’s name. This way I could go back and dive deeper into their work and mythology.

For my own reasons, I want all my pictures of art completely unfettered - all pixels and RBG splendor in their full detail. On the other hand, the pictures of text have a lot of unnecessary information. The real critical information is the name of a person. Therein, my problem is defined: how can I identify pictures of text and remove non-critical information?

A Primer on Principal Component Analysis

I want to give a brief and mostly non-technical primer on the real workhorse in this solution: Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA is a linear transformation technique used to identify the principal components of the data — these are orthogonal directions (eigenvectors of the data’s covariance matrix) that capture the greatest variance. By projecting the data onto these components, PCA effectively reorients the data to highlight its most informative structure.

Take this visual explanation. In a 2D space, we make a linear transformation of the data such that it can be explained by two principal components. However, PC1 really does the bulk of the explaining and thus we can save space if we omit detail regarding PC2. Here’s an easier to understand analogy: if I’m walking along a plain in the flatlands of Kansas, I’m still in a 3D space. We describe my 3D walk in terms of walking forward/backward, left/right, and up/down. But there’s not going to be any meaningful change in elevation since I’m walking in a plain. Instead of using all 3 dimensions to describe my walk, I’ll leave out any details of elevation to not bloat the conversation with unnecessary data. That’s a high level simplification of PCA

Watching PCA Downsampling in Action

Similarly, in a much higher dimensional space, we can apply PCA to downsample my pictures from vacation. Here are two .gifs I made of a picture of a painting (a portrait of Salomon Beffie by Jan Sluijters) and its corresponding text label.

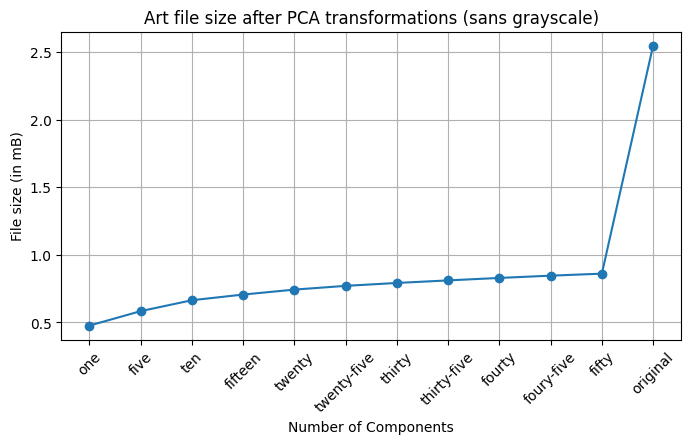

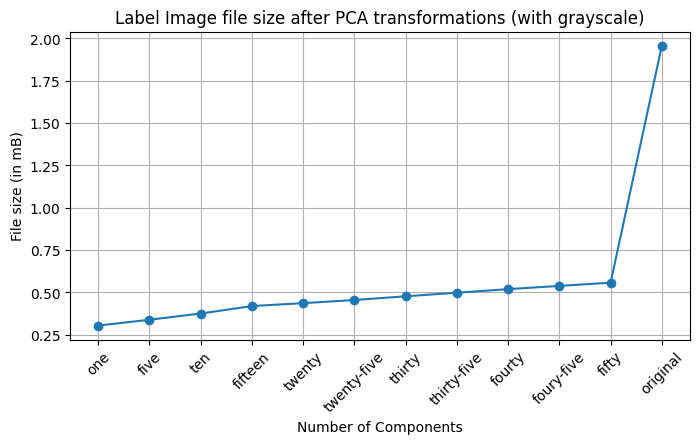

In these .gifs, I show what downsampling to 1 through 50 principal components looks like (in intervals of 5), concluding with the original photo for comparison. Also provided are line charts showing the file size of each iteration and then lastly the original file size. Note: the text photo downsampling also includes conversion to grayscale as this is another method of space-saving that can be included for the intention of the image.

As you can see, PCA is a really effective method to reduce a set of data (in this case, a picture - which is just an array of pixel values) into the features that capture the most variability. While I won’t be doing this in practice to the artwork, we can see that at a cursory glance we can keep the general gist of the image at just around 30 components. Actually, if all you needed to know was the picture was of some shape that had colors, 1 component could tell you as much. Similarly, some of the text in the label begins being legible at just around 15 components. For either instance, the size saving going from the original image to even 50 components is massive.

The Process Explained & Final Results

In 7 months of traveling I have generated 565 (1.6gb) pictures of art or corresponding labels. I wanted to significantly reduce the file sizes of the text labels by

- Converting these to grayscale images

- Cropping to the relevant text

- Downsampling to 50 principal components

Prior to these steps, I used OpenAI’s Contrastive Label Image Processing (CLIP) model to determine which pictures are of art and which are of text. For the cropping step, I used PyTesseract to identify the text through Optical Character Recognition and then cropped the image to the bounding box the text was in. This did not work reliably (often overcropping or failing to detect text), so I added some padding and undid this step if the cropped area was too small. Finally I applied the 50 principal component downsampling.

Starting from a corpus size of 1.6gb (including art pictures), I was able to shrink this to a size of 1.2gb. This is a near 25% savings. This is considerably smaller than the 75% savings when shrinking and individual picture from about 2mb to 0.5mb, but it must be considered that I often only took one text label photo of an artist name to be used for several art pictures if those were from the same artist (when shown as one collection or a retrospective). If you want to reproduce this project, or adapt it for you own photos, the GitHub repo is here.

Conclusion

This is not the optimal solution to create some space on my phone. As I’d mentioned before, if I really wanted to free up space I’d move these photos to some external storage. If I wanted to keep them on my phone, even this is not the optimal solution. I could simply delete all the text label photos and use Google Lens anytime I wanted to recall who the artist of a particular piece is. Looking outside this art/label corpus, I think I might have some other instances of photos that are very similar and serve no use having them all on my phone (upcoming similarity and recommendation project coming soon?). Mostly, this was an opportunity to employ a technique I learned in grad school, teach others about that technique (at a cursory level), and try out some new technologies I haven’t encountered before.